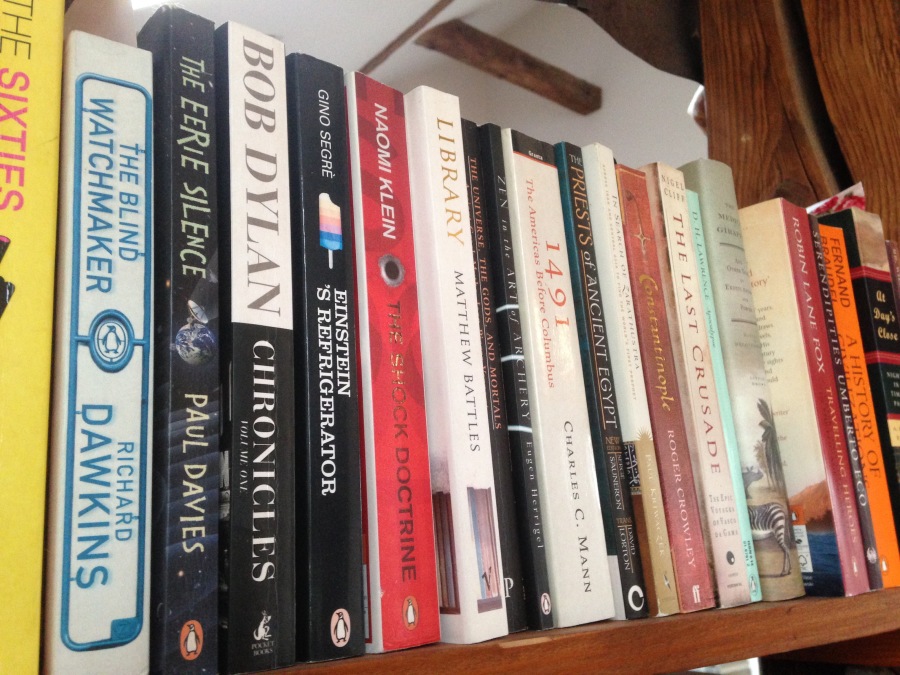

One of the great things about the personal connection in doing Airbnb (or similar) is that, if you’re lucky, some of the places might have interesting art, music or books. This place in Ljubljana has books, most in English, most about history. I do have some books on my phone but I don’t want to be squinting at this device ALL day so it’s nice to have a browse with a cup of tea.

I wanted to find out more about the experience of countries like Slovenia, Slovakia and Hungary in the past century. I discovered just how much the Slovenians suffered under the Nazis and then the Russians, and how their population depleted.

Mostly I’ve been searching out nuggets about the formation, and the idea of, Europe.

Robert Service in ‘Comrades’ (about the history of communism) writes about the formation and Soviet hegemonisation of Eastern Europe and how each country differed in its resistance or acceptance of communism and Soviet control. Where it seems people were more compliant is in places where the economy was more free for people to run their own small enterprises (e.g. Hungary).

He writes “Communism for Western Europe – with Italy, France, Spain and Greece as notable exceptions – held next to no appeal to the imagination of the industrial working class in whose name it had been invented.”

Yesterday I went to Ljubljana’s excellent Ethnographic Museum and saw this quote:

“In the Mosaic of the world between the near and far, between the past and the present, between the known and the unknown, between the real and imaginary I search for my place.”

The exhibition was asking questions such as ‘why do we feel such a strong need to belong?’ It was done very sensitively and with an open mind. But I wonder if we make too much of this notion of belonging, when it boils down to a need to live in a habitat that is favourable to our needs, to live in a way that continues being favourable to our needs, and not to be imprisoned or exiled from it? Maybe a politics of conflict over territory sits alongside a romanticisation of identity that denies ecological realities?

A huge influence on contemporary thinking about identity arises from a wounded response to that international trauma, the rise and defeat of the Nazis.

Mark Makower’s Hitler’s Empire: How the Nazis Ruled Europe has an excellent section on We Europeans. He argued that “Hitler was…the most European of the leading statesmen of the Second World War…he did have a conception of Europe as a single entity, pitted against the USSR on the one hand, and the USA on the other.”

British Eurosceptics have suggested that the EU is a Nazi dream come true, but Makower explains how wrong they are. Hitler’s idea, despite early lip-service to a vision of free and independent states, became a will for a Europe totally under German hegemony, aiming to provide land for the notionally burgeoning German people. Hitler preoccupied himself with plans for creating utopian German towns. He didn’t care to admit diverse ethnicities into this vision and saw the Slavs as invaders from the East. ‘The SS would wipe out the Jews and later sort out the Slavs as well.’

Makower describes all the proposals by exiled governments and Allied policy makers that were federalist and unifying, but none made it beyond treaty stage. People, especially those under Nazi occupation, were acquiring a greater desire for national independence which a federated Europe would not serve. Also Stalin wouldn’t agree to any scheme that created a strong European bloc. After Hitler died lots of pan- European organisations were formed to aid recovery, and then in 1946 Churchill proposed a ‘United States of Europe’. In 1949 the Council of Europe “articulated an idea of Europe as a law-bound and rights-governed community that was defined both against the still vivid memory of Nazi occupation and against the threat posed by Soviet totalitarianism.” Markover explains how it was really the coming together as a response to Nazism that formed what Europe is today, and that its not Hitler’s dream child.

But when did the idea of Europe start and how long has there been a common continental identity, if such a thing has ever been? More digging further back in time followed, into Chris Wickham’s ‘The Inheritance of Rome: A History of Europe from 400 to 1000.’

Wickham writes: ‘Early mediaeval Europe has, over and over, been misunderstood. It has fallen victim above all to two grand narratives, both highly influential in the history …of the last two centuries, and both of which have led to a false image of this period: the narrative of nationalism and the narrative of modernity… Europe was not born in the early Middle Ages… there was no common European culture, and certainly not any Europewide economy. There was no sign whatsoever that Europe would, in a still rather distant future, develop economically and militarily so as to be able to dominate the world… National identities…were not widely prominent in 1000…’

He says that where there was some strong sense of ‘national’ identity it was helped by either geographical isolation or a strong coherent political system e.g. in Byzantium.

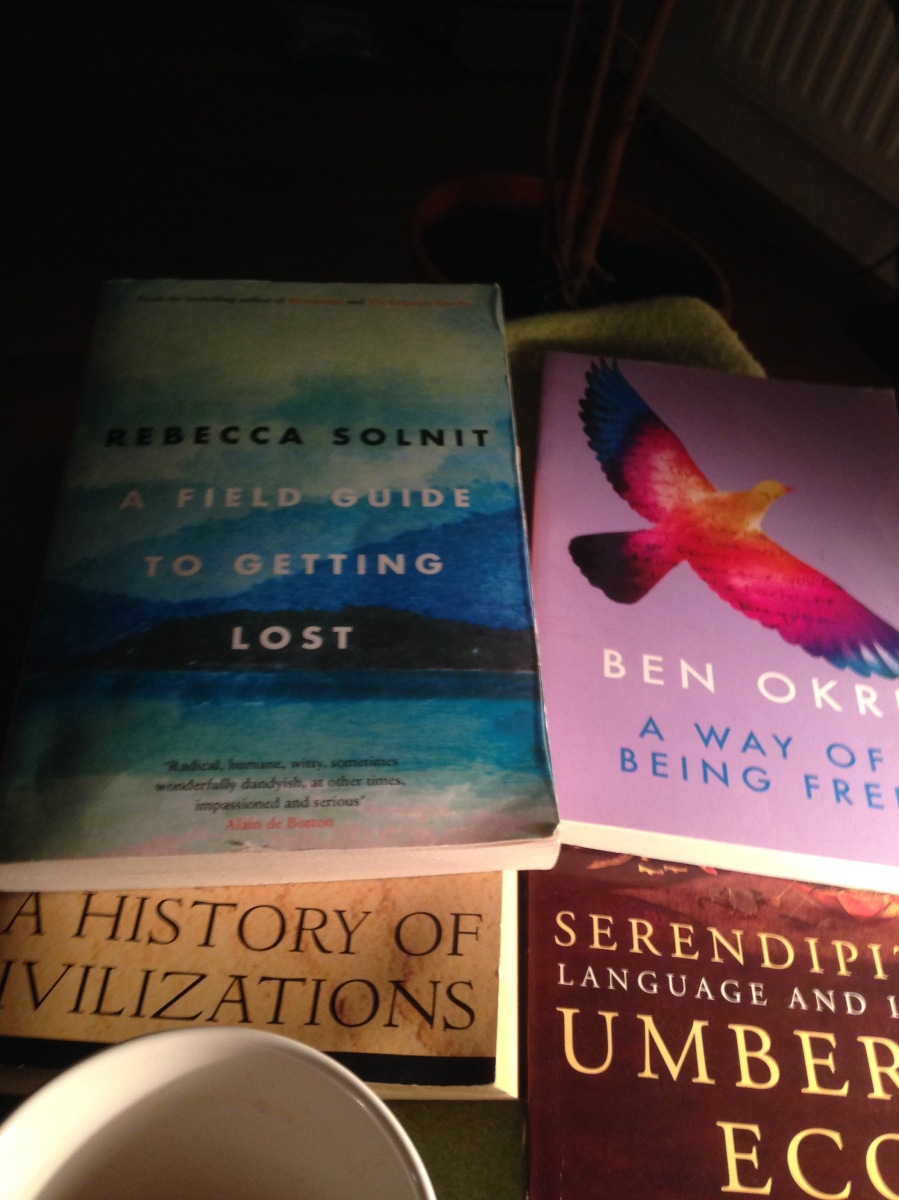

Then I had a go at Fernand Braudel’s ‘A History of Civilisation’, essentially an educational textbook written circa 1960. This is from his chapter on Unity in Europe:

‘…A number of things (are) shared by the whole of Europe: its religion, its rationalist philosophy, its development of science and technology, its taste for revolution and social justice, its imperial adventures. At any moment, however, it is easy to go beyond this apparent ‘harmony’ and find the national diversity that underlies it. Such differences are abundant, vigourous and necessary. But they exist just as much between Brittany and Alsace, between the North and the South of France, between Piedmont and the Italian Mezzogiorno; between Bavaria and Prussia; between Scotland and England; between Flemings and Walloons in Belgium; or among Catalonia, Castille and Andalusia. And they are not used as arguments to deny the national unity of each of the countries concerned….

Nor are these national instances of unity a contradiction of Europe’s own. Every State has always tended to form its own cultural world…(but) broadly speaking Europe is a fairly coherent cultural whole…. Europe has had a single philosophy, or something very like it, at every stage of its development…

As regards the natural sciences, there can be no question: they were strictly pan-European from the time of the first success’. (In comparison, Braudel explains, the arts based on language tend to have more national or local differences.)

He goes on: ‘For centuries, Europe has been in meshed in what has amounted to a single economy. At any given moment, it’s material life has been dominated by particular centres of privilege and influence…very early on, Europe became a coherent material and geographical whole, with an adaptable monetary economy busy communications along its coasts and rivers and then via the carriageways and roads for pack animals that complemented its natural thoroughfares.’

So he differs from Wickham (who resists the common European narrative) but mainly because he is focusing more on the modern period but perhaps also because he is being didactic for a French readership.

He goes on to talk about the formation of the EU project – in a way that is tentative and hopeful. He concludes that politics is the barrier and the key: ‘Invited to build European unity, culture responds readily; the economy is more or less willing; only politics drags its feet… The truth is that all of Europe has long been involved in the same political system, from which no State could escape without grave risks to itself.’

What is missing from this lagging politics (or was in c.1960) is a fundamental ethos that is built on culture. Braudel says that those building Europe are obsessed with customs duties, prices and production levels. ‘It is disturbing to note that Europe as a cultural ideal and objective is the last item on the current agenda… Europe will not be built unless it draws upon those old forces that first formed it and still moves within it: in a word, unless it calls for the many forms of humanism that it contains.’

He says that for many people at that time the aim was to regroup Europe against the Soviet danger, and this was clearly the American policy. Interesting to be thinking about all this just as Trump appears to be switching position on Russia and NATO, whether this is just managing our perceptions in collusion with Russia, or him flipflopping completely out of his depth, your something else entirely, we wait to see.